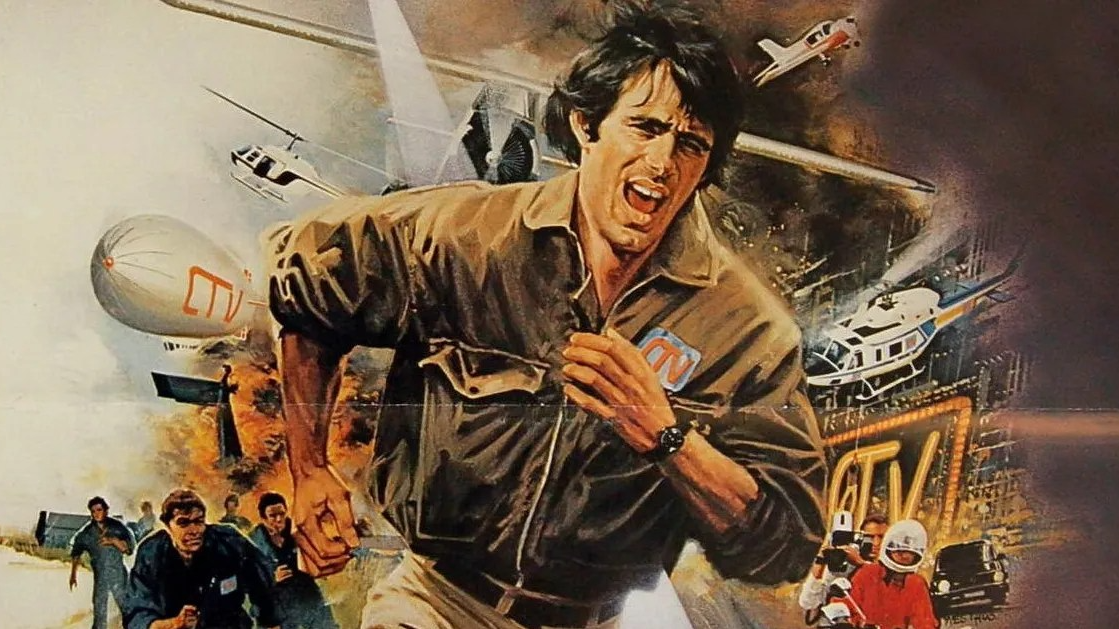

When The Running Man arrived in cinemas, it looked like another Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle. Bright colours. Broad villains. Catchphrases delivered like blunt instruments.

But, as discussed in Rewind Classic Movies S2E05, this wasn’t just a case of an adaptation drifting from its source. This was a film that fundamentally changed direction, tone, and intent partway through development. What began as one kind of movie became something else entirely, and the seams are still visible.

Here are six key areas where The Running Man reveals what it was – and what it stopped trying to be.

You can also listen to the full podcast episode below, or whoever you get your podcasts.

1. A Stephen King Story That Didn’t Want to Be Stephen King

Stephen King’s original novel is bleak, angry, and mean-spirited. The world is broken. Television is cruel by design. There is no joy, no hero worship and no clean ending.

The film keeps the idea of televised punishment, but discards almost everything else. What replaces it is a version of dystopia that feels oddly safe. The violence is exaggerated but rarely upsetting. The suffering is theatrical. Even the oppression is glossy.

As discussed in the episode, this creates a tonal contradiction. The film wants to warn about media manipulation and authoritarian control, yet constantly undercuts that message with spectacle and humour. The result isn’t satire so much as a theme park version of danger.

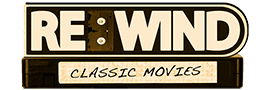

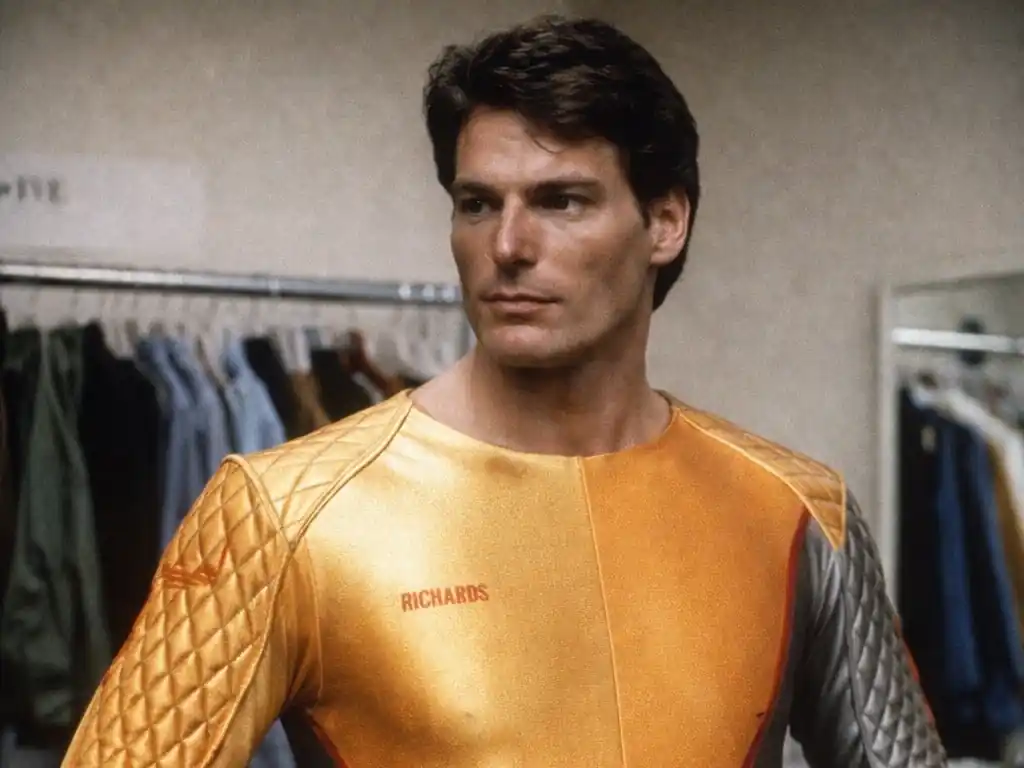

2. Why Christopher Reeve Leaving Changed Everything

One of the most important points raised in the episode is how dramatically the film shifted once Christopher Reeve exited the project.

Reeve was originally attached to star and his presence implies a very different movie. A lighter physicality. A more everyman hero. A version of The Running Man closer to thriller than action circus.

Once Reeve left and Arnold Schwarzenegger took over, the film had no choice but to adapt to him. Schwarzenegger couldn’t plausibly play a desperate, starving man ground down by the system. He is the system’s nightmare, not its victim.

So the script changed. The tone changed. The satire softened. The character became indestructible. The movie stopped asking “what does this world do to people?” and started asking “how many one-liners can we fit between explosions?”

This wasn’t a creative preference. It was a necessity.

READ THE FULL STORY HERE: Why The Running Man Had to Change When Christopher Reeve Left

3. Arnie, One-Liners, and the Limits of the Persona

The episode is clear-eyed about Schwarzenegger’s strengths and weaknesses. He looks phenomenal, sells the physicality and dominates the frame.

But The Running Man leans so heavily into his persona that it flattens the story. The jokes arrive too often. The kills are framed as punchlines (“he had to split”, etc). Any sense of fear dissolves because the outcome is never in doubt.

It works on a surface level, but drains tension from scenes that should feel brutal or tragic. The film wants the audience to cheer, not reflect. That decision defines everything that follows.

COME BACK TO: 10 Classic Movie Cops Who Were as Clueless as Frank Drebin (Feat. Arnold Schwarzenegger)

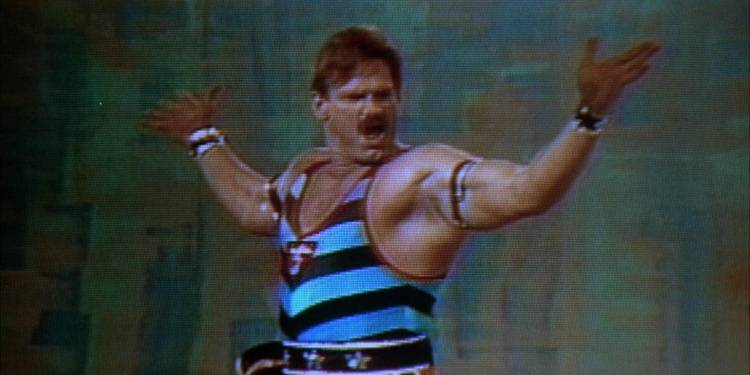

4. Violence Without Consequences

Despite its reputation, The Running Man is not especially violent in emotional terms. The deaths are stylised. The antagonists are cartoonish. The suffering is abstract (one of GB’s favourite scenes was, weirdly, one of the bad guys being sawed through the balls as his scream gets higher).

As discussed in the podcast, this makes the film oddly toothless. A story about state-sanctioned murder becomes an exercise in set-pieces. Even when the body count rises, the impact never does.

Compared to other dystopian films of the era, this one feels curiously uninterested in aftermath. People die. The show continues. The audience moves on. Which, unintentionally, mirrors the behaviour the film is supposedly criticising.

5. A Film That Accidentally Predicted Reality TV

For all its compromises, The Running Man gets one thing uncomfortably right. The mechanics of television. The packaging of cruelty as entertainment. The way narrative is shaped to protect power.

The episode notes that this aspect has aged better than the action (and the editing). Not because the film is subtle, but because reality eventually caught up with it. The manipulation of footage, the creation of villains, the performance of outrage. All familiar now.

What the film lacks in depth, it compensates for in accidental foresight.

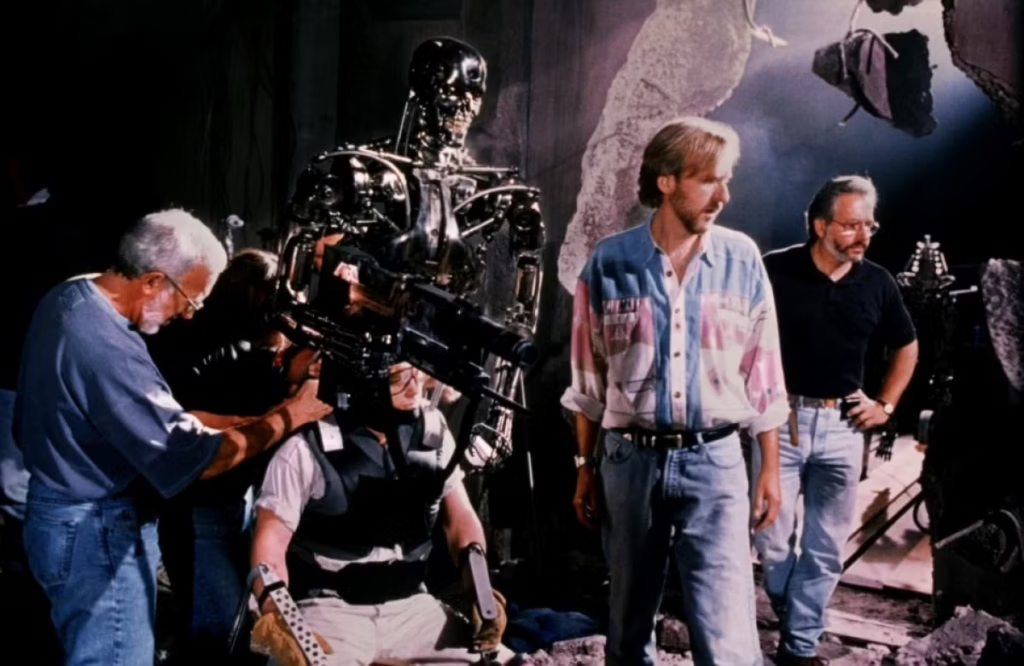

YOU MIGHT LIKE: Terminator’s $24m mini T2 sequel & abandoned trilogies

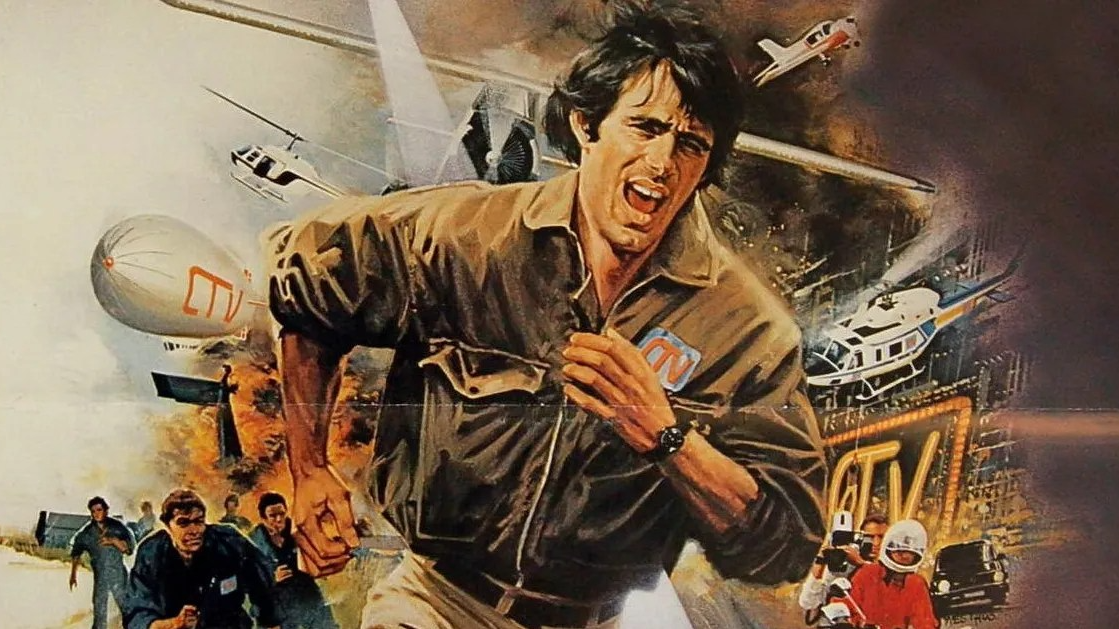

6. The Lawsuit That Exposed the Film’s Complicated Origins

Beyond its troubled adaptation and tonal shifts, The Running Man also arrived with a legal shadow that highlighted just how crowded its conceptual territory already was.

The lawsuit associated with the film did not come from Stephen King. Instead, it stemmed from similarities to earlier screen works that had explored almost the same premise years before. Most notably, the 1983 French film Le Prix de Danger, directed by Yves Boisset, depicted a near-identical idea – a man hunted for sport in a televised game show, with violence repackaged as entertainment.

That film itself was adapted from Robert Sheckley’s 1958 short story The Prize of Peril, and similar concepts had already appeared on television, including the 1970 German production Das Millionenspiel. By the time The Running Manreached cinemas, the idea of media-driven manhunts was no longer unique, even if the Hollywood execution was louder and more polished.

Boisset pursued legal action over the similarities, and the case was eventually settled, with compensation paid years later. However, the settlement reportedly came only after a long legal process, and the damages were modest, barely covering the cost of bringing the case in the first place.

The lawsuit matters less for its outcome than for what it reveals. The Running Man was not just an adaptation that drifted from its source material. It was a film operating in a space where multiple creators had already explored the same dystopian fears, and where ownership of the idea itself was far from clear.

A Unique Blend That Created An Iconic Oddity

The Running Man is not a failed film, but it is a divided one. A project pulled between source material, star power, and commercial instinct. You can see the moment it changes course, and you can feel what was lost along the way.

It remains entertaining. It remains iconic. Sort of. But as discussed in the Rewind episode of the podcast, it’s most interesting as a case study in how casting alone can reshape an entire movie’s DNA.

Sometimes the future isn’t rewritten by ideas.

Occasionally it’s rewritten by muscles.

READ NEXT: How The Terminator Was a Bargain in 1984 — And Where They Saved Every $